Found Artifacts

Over the recent years, thousands of artifacts have been found.

Along a stream, carved rock bowls had been turned over and left by the Atfalati being too heavy to carry during their migrations.

Located near the water’s edge, the bowls could be easily found when the Atfalati returned on their seasonal rounds. Bowls were turned right side up, washed in the stream and ready for use. Berries were often mixed with pounded watato roots and made into cakes.

Some found artifacts reveal bowls with carved designs.

Years later, farmers plowing their fields unearthed bowls, tools and other long ago treasures.

Very early settlers recall the Atfalati burning the fields in the fall, a tradition which had been done for centuries.

Splitting Wedge 6 1/2 inches (right)

Triangular Pestle (lower right)

Artifacts, Buehler Collection

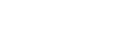

Atfalati Encampment Names

Chachimahiyuk “Place of Aromatic Herbs” [geographic name, Tigard —near what was known as Progress, wild mint grew in the area. The campsite was in the shelter of a rocky knoll. There was also a spring from which pure water flowed.]

Chaginduefti [band living between McKay Creek and Sauvie Island.]

Chakeipi (Tch’′akéipi,) “Place of the Beaver” before the treaty of 1855. Gatschet [geographic name, Beaverton —with the greatest concentration of artifacts found on the dry land just north of the swamps or “beaverdams” was near the area called Marlene Village.]

Chapanaghtin [geographic name, Glencoe]

Chatakuin “Place of the Big Trees” [geographic name, Five Oaks located off the Sunset Highway. Take Jacobson Road and wind around to a kiosk showing the history.] See also Chatakuin.

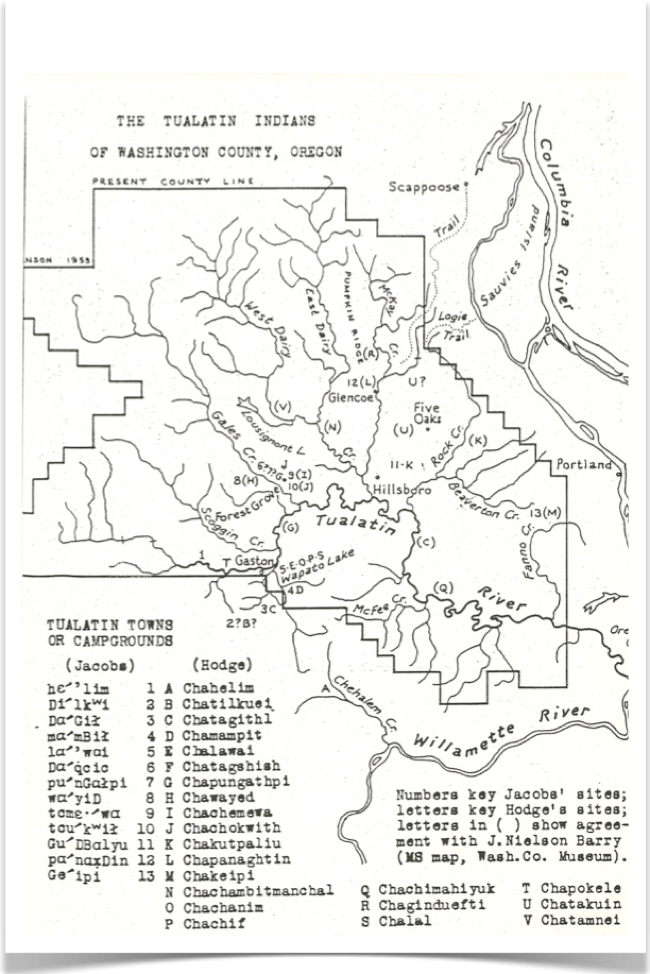

Washington County Petroglyphs

These are the only important group of Atfalati rock carvings in Western Oregon discovered in 1878.

The petroglyphs on this steep sandstone cliff cover a distance of about 35 feet with the highest point being 11 feet. The rock has many carvings and designs however they can not be seen because of the thick green moss coating the stone.

Emphasis on eyes and the rays from the head are familiar Pacific Northwest Coastal tribe traits.

Rock Rubbings by Rachael W. Kester

Carvings

Moss and lichen growth on the petroglyphs found on the steep sandstone ridge may indicate centuries since these carvings were done. Moss and lichen cover about 90% of the petroglyphs. Over the years this has been rubbed off repeatedly by those seeking the images.

Weathering has also worn away some of the detail in the sandstone carvings.

The figures emphasize the head and shoulder area. Sometimes the body is represented by a long groove. Some show arms and fingers.

Many years ago part of the Indian carvings were defaced on one end of this display. For this reason the exact location of the site is not public information and it is located on private property.

Professional rubbings were done by Rachael W. Kester and show more detail from those earlier years.

Here is a hole that goes about 8 inches deep into the rock. Perhaps this would be a base for a staff that stuck out as a signal or held a hanging display?

Indian Lore:

Could this cliff have been like a sign board along the trail to the coast?

Was this stone rock the dividing line between the coast and the valley Indians?

Hole with moss cleared away.

The same opening covered with moss.

Ron Mapes photo

On the figure above is an arm and

a three-fingered hand bent downward from

the elbow. The humerus extending at an

angle from the body.

Ron Mapes photos

Corey Mitchell photo

Lewis & Clark 1805-06

Lewis and Clark’s overland journey to the Pacific Northwest, reported a wealth of fur-bearing animals in the region. Paddling down the Columbia River, Clark noted several large Indian villages and saw smaller encampments on “Wappatoo Island,” [Sauvie Island.] They traded with the permanent dwellers as well as the visitors who had come to fish and dig wapato roots.

Fort Vancouver 1825

Hudson’s Bay Company established Fort Vancouver in 1825 and controlled the fur trade. Mountain men were trapping in our area during the late 1820s and into the 1830s.

August, 1830 — Sickness

Scottish naturalist David Douglas wandered the Pacific Northwest coast gathering botanical samples for the London Horticultural Society. Returning to Fort Vancouver after a three-week sojourn down the Willamette River he found a terrible epidemic spreading through the post. By the end of September nearly half the people including Douglas and the new fort doctor were afflicted. It was known as “fever and ague” or “intermittent fever.”

I am one of the very few persons among the Hudson Bay Company’s people who have stood it, and sometimes I think, even I have got a great shake, and can hardly consider myself out of danger, as the weather is yet very hot.

Most of the Canadian staff and mixed-blood families at Fort Vancouver recovered. The Hawaiian and Indians were hit the hardest. Large numbers of Indians from surrounding villages came to camp near the post for help. Deaths were overwhelming.

In 1830 when the big epidemic struck, most of the outlying Atfalati settlements were abandoned and the surviving people consolidated with the central villages around Wapato Lake.

In October Douglas sent a letter back to England, “Villages, which had afforded…two hundred effective warriors are totally gone, not a soul remains!”

1840

By 1840 the beaver were gone and so were most of the Atfalati People. Some survivors continued to make their seasonal rounds. Some remained to integrate with the white community.

April 19, 1851 Treaty

Atfalati ceded their lands in return for a small reservation at Wapato Lake as well as money, clothing, blankets, tools, rifles, and a horse for each of their headmen—Kaicut, La Medicine, and Knolah. There were only 65 Atfalati left at that time. The treaty was never ratified.

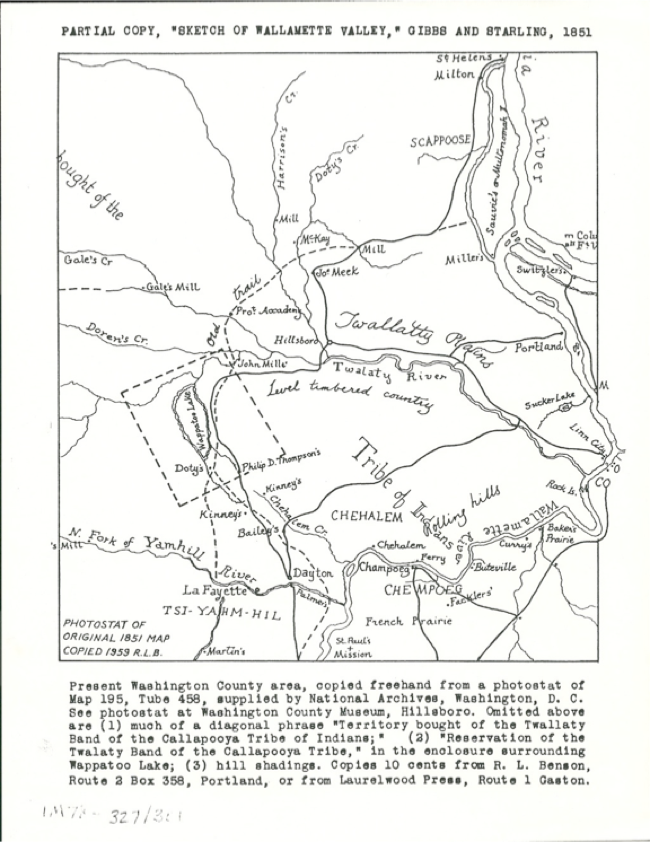

Robert L. Benson map Small Reservation at Wapato Lake _ _ _ _ _

January 4, 1855 — Treaty (10 Stat. 1143, ratified March 3, 1855), the Atfalati were to live in the Willamette Valley until a suitable reservation was designated as their permanent home. In 1870 census cited 60 living on the Grand Ronde reservation, the permanent home assigned them by the government.